Statute of limitations in international arbitration – Vietnam perspective

The statute of limitations, defining the timeframe within which legal action must be initiated, plays a pivotal role in ensuring justice and protecting parties’ rights in international arbitration.

This article examines the application of the statute of limitations in arbitration from Vietnam’s perspective, where its characterization as substantive or procedural remains unclear, influencing the setting aside or refusing recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards. Through detailed analysis, the authors explore the complexities of identifying applicable laws under Vietnamese law — such as the Civil Code, Commercial Law, or Law on Commercial Arbitration regarding the statute of limitations and the significant implications of this determination. The article further highlights the strategic importance of exceptions to limitation periods, including exclusions or events that restart the statute of limitations, particularly when the statute of limitations appears to have expired.

While focusing on the analysis of the statute of limitations in arbitration proceedings, this article also examines the starting point of the limitation period for initiating legal action when a construction contract is governed by the FIDIC Suite under its Dispute Settlement provisions, offering a focused commentary on a globally contentious issue within Vietnam’s legal context.

Download PDF file is here

Vietnam’s diverse legal framework governing the statute of limitations

While the determination of the statute of limitations is straightforward in domestic arbitration, where the applicable law (such as the Civil Code) is clearly defined, international arbitration often involves multiple potentially relevant legal systems, making this determination significantly more complex.

Specifically, under civil law system, the statute of limitations is treated as a substantive issue, focusing on the subjective right to the claim. In the common law system, statute of limitations or the limitation of actions focuses primarily on the process, rather than on the issue or claim presented.[1]

Brian Millar, in his work further noted that a trend has emerged in doctrine and arbitral case law establishing that, in international arbitration, the statute of limitations is governed by the law applicable to the merits of the dispute (the lex causae or lex contractus), irrespective of the mandatory provisions of the lex arbitri. United Kingdom and Singapore are the common law jurisdictions but treat the statute of limitations as substantive law.[2] Australia and Canada also have moved away from treating statute of limitations as substantive rather than procedural. However, in other common law jurisdictions such as Hong Kong, India, and Malaysia, statute of limitations are still considered matters of procedural law.[3]

Perspectives of several Jurisdictions on the Statute of Limitations

Vietnam, as a civil law system with a diverse legal framework governing the statute of limitations, does not clearly define whether it considers the statute of limitations as substantive law or procedural law.

Statute of limitations is?

In fact, the statute of limitations appears in both substantive laws, such as the Civil Code 2015 (“Civil Code”) and the Law on Commerce 2005 (“Commercial Law”), as well as in procedural law, such as the Law on Commercial Arbitration 2010 (“LCA”). More importantly, these laws differ in their provisions on statute of limitations, adding to the complexity of the issue and sparking considerable debate.

Delving deeper, in light of Art. 671 and Art. 6831, Civil Code, the statute of limitations for civil relations involving foreign elements is determined based on the parties’ mutual agreement. These provisions respectively state that “the statute of limitations for civil relations involving foreign elements shall be determined according to the applicable law for such civil relations” and that “contracting parties in a contract [with foreign elements] may agree to select the applicable law for the contract.”

However, the LCA does not take the same approach as the Civil Code. While Article 14.2 allows the parties to choose the applicable law for the contract, it does not explicitly grant them the ability to select the applicable law for the statute of limitations. Article 33 of the LCA, which addresses statute of limitations, makes no distinction between disputes involving foreign elements and domestic disputes. As a result, it is interpreted that the statute of limitations under Article 33 applies universally to all disputes, meaning that parties are not empowered to choose the applicable law for this issue.

Another notable issue is that even when Vietnamese law is determined as the governing law – either through choice of law or legal reference – it is not necessarily straightforward to conclude that the statute of limitations under the LCA will apply. Art. 33, LCA explicitly states that its provisions on statute of limitations apply only in the absence of contrary provisions in specialized laws.

Therefore, under Vietnamese law, it remains unclear whether substantive or procedural law applies to determine the statute of limitations when a dispute arises and is brought before a tribunal in international arbitration.

The application of the statute of limitations in Vietnam is dynamic and evolving

Perhaps due to inconsistencies among various laws governing the statute of limitations, its application in Vietnam remains dynamic and evolving, creating significant challenges.

Firstly, from a scholarly perspective, the question of whether the statute of limitations is treated as substantive or procedural law remains unresolved. This is evidenced by the differing viewpoints highlighted in the article titled “Thời hiệu khởi kiện thuộc pháp luật nội dung hay pháp luật tố tụng – Đôi điều kiến nghị” of, Former Deputy Chief Justice, Tuong Duy Luong.

Secondly, from a practical perspective, Vietnamese courts have adopted different approaches to this issue. For example, in Decision No. 11/2018/QD-PQTT dated 12/10/2018 of the People’s Court of Hanoi, a party sought to set aside an arbitral award on the grounds that the two-year statute of limitations under the LCA had expired. However, the Court ruled that the statute of limitations had already been determined by the arbitral tribunal in its award and was therefore considered a matter of substantive law. As a result, the Court declined to review the substance of the dispute, including the statute of limitations, in accordance with Article 71.1 of the LCA. Furthermore, the Decision also held that the statute of limitations is not a fundamental principle of Vietnamese law that would warrant the setting aside of an arbitral award.[4]

In contrast, in Decision No. 1109/2018/QD-PQTT dated 16/08/2018, the People’s Court of Ho Chi Minh City took the approach that the statute of limitations are matters of procedural law, as such, the Courts are allowed to review such matters in their assessment of setting aside arbitral awards.[5]

The application of the statute of limitations remains ambiguous, posing a significant challenge for arbitral tribunals facing objections based on the expiration of statute of limitations. The tribunal’s classification of a given statute of limitations as either substantive or procedural carries far-reaching implications under Vietnamese law, particularly in the two areas discussed below.

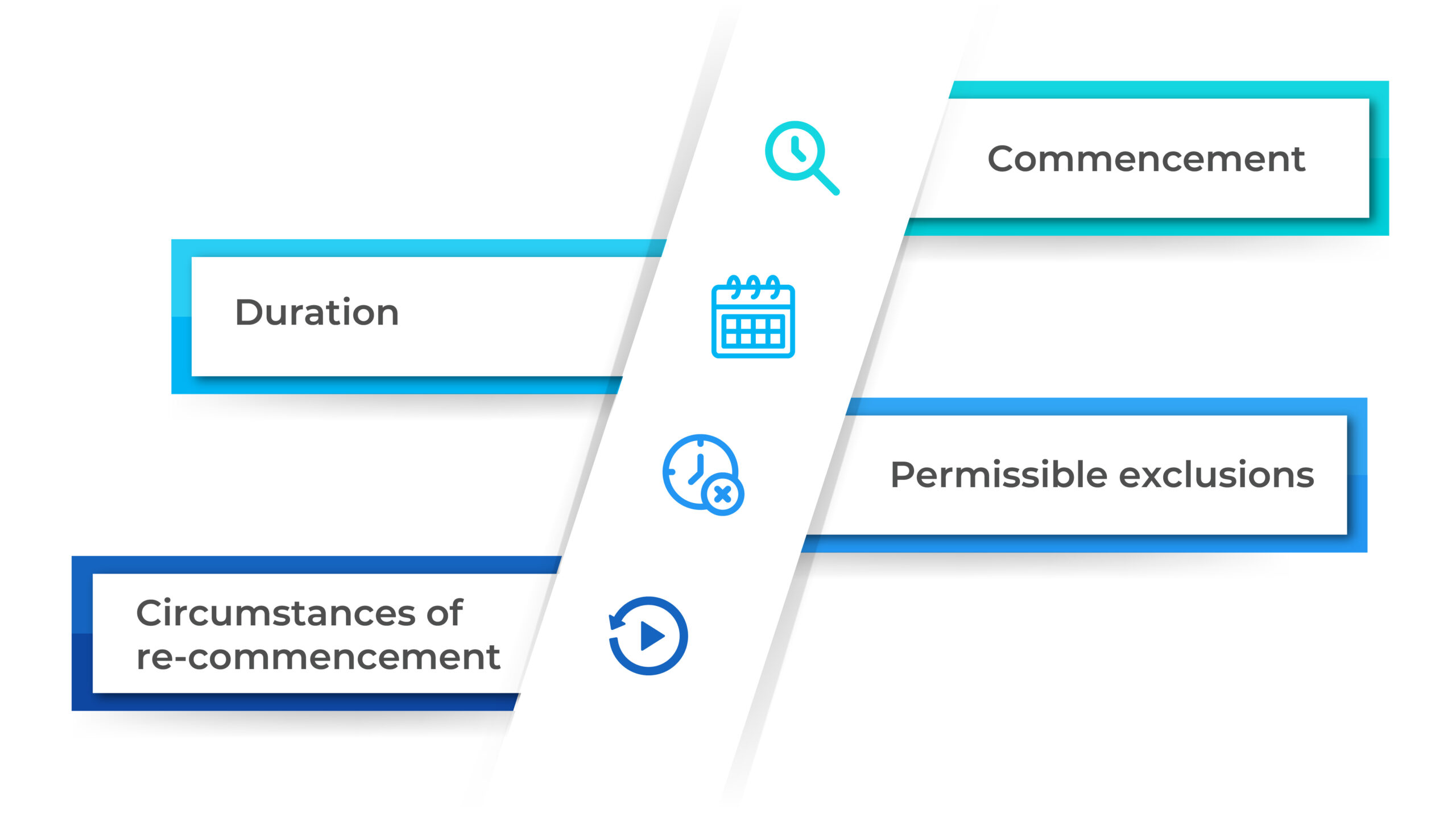

First, the classification of statute of limitations as substantive or procedural directly impacts the determination of the applicable law governing various aspects of the statute of limitations, including its commencement, duration, permissible exclusions, and circumstances of re-commencement. This issue has been posted by Prof. Do Van Dai in a journal, saying “If the statute of limitations is governed by the law of arbitration, the statute of limitations is the same for all types of disputes. Conversely, if the statute of limitations is governed by the substantive law, the statute of limitations may vary from case to case because the substantive law may be different in each case even though it is resolved by arbitration.”[6]

The various aspects of the statute of limitations

Specifically, if the statute of limitations are considered matters of substantive law, they would be regulated by the applicable law for the underlying contract as agreed by the parties, or as determined by the arbitral tribunal in the event of the absence of agreement by the parties. Conversely, if the statute of limitations is considered a matters of procedural law, they would be regulated by the Vietnamese law. Given that the applicable law for the dispute in international arbitration often diverges from Vietnamese law, the law applicable to statute of limitations, and therefore their practical effect, will necessarily vary depending on the specific circumstances of each case, leading to potentially disparate legal consequences.

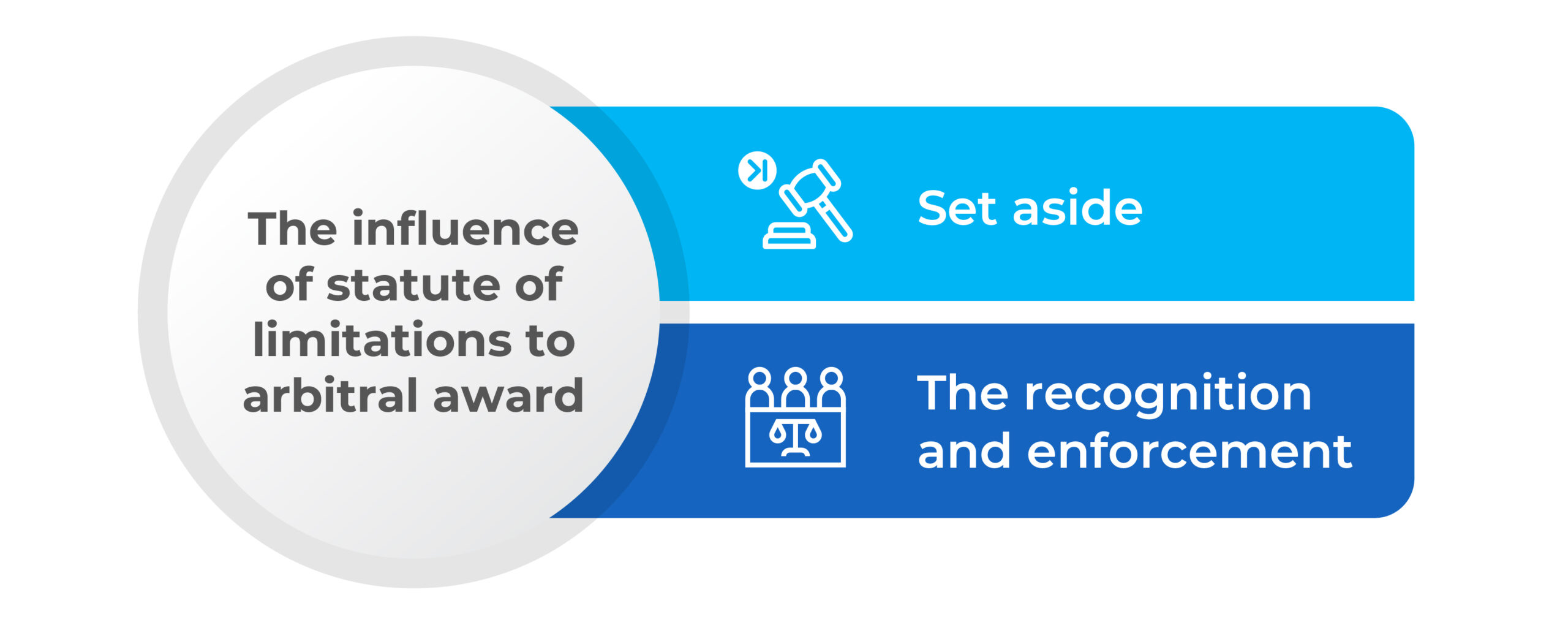

Second, the determination of whether statute of limitations are matters of substantive or procedural law greatly influences the possibility of awards being set aside or refused for recognition and enforcement.

The influence of statute of limitations to arbitral award

Accordingly, if statute of limitations are considered matters of substantive law, the Courts of Vietnam would not be able to review the content resolved by the arbitral tribunal[7], as such, statute of limitations could not be a pretext for the courts of Vietnam to set aside (in case of domestic arbitral award) or refuse the recognition and enforcement (in case of foreign arbitral award). In this aspect, the law of Vietnam is fundamentally the same as Article 34 and Article 36 of the UNCITRAL Model Law, as well as Article 5 of the New York Convention.

On the other hand, if the statute of limitations are considered matters of procedural law, it could be a pretext for one of the disputing parties to request the courts of Vietnam to set aside arbitral awards under Article 68.2(b) of LCA (which adopts a principle similar to that of Article 34.2(a)(iv) of the Model Law) or refuse the recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards under Article 459.1(dd) of the Civil Procedure Code 2015 (which adopts a principle similar to that of Article 36.1(a)(iv) of the UNCITRAL Model Law and Article 5.1(d) of the New York Convention).

An Analysis of Statutes of Limitations under Vietnamese Law

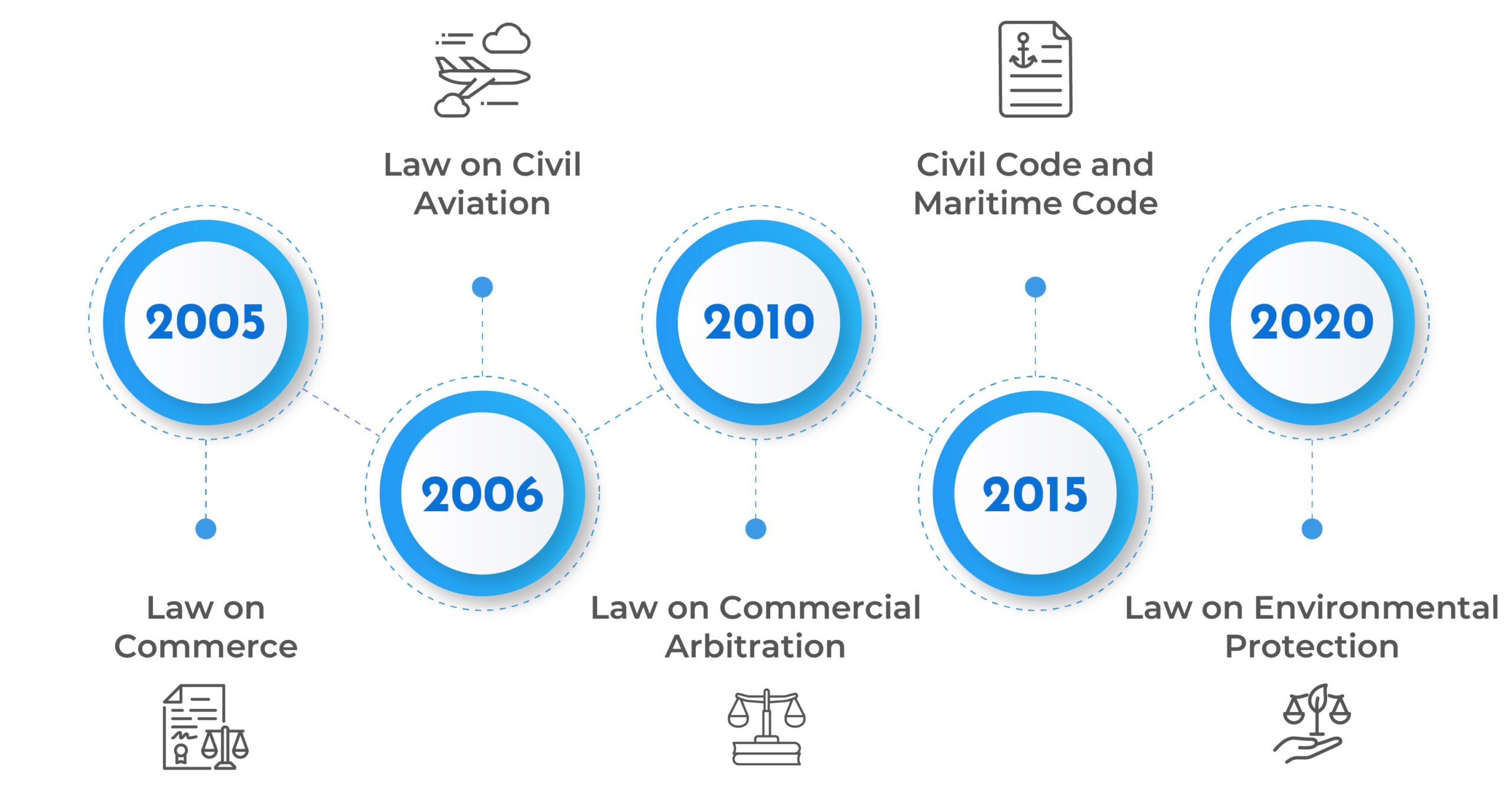

As previously mentioned, the application of the statute of limitations in international arbitration in Vietnam is not straightforward, as multiple laws may be relevant depending on the specific case. These include the Civil Code 2015, Commercial Law 2005, Law on Commercial Arbitration 2010, Maritime Code 2015, Law on Environmental Protection 2020, and Law on Civil Aviation 2006, among others. Consequently, each law may have different provisions on the statute of limitations.

The Vietnamese legislative documents have provisions regarding statute of limitations

In this paper, we analyze the statute of limitations in the context of the Civil Code, the Commercial Law, and the LCA, as these are the most frequently applied laws for addressing this issue within the Vietnamese legal framework.

The table below provides an overview of the statute of limitations applicable under each law.

| Criteria | Civil Code 2015 | Law on Commerce 2005 | Law on Commercial Arbitration 2010 (LCA) |

| Role | The general law for civil relations | The specialized law governing business and commercial relations

|

The Law governing dispute resolution via arbitration in general, including the arbitration procedures |

| Duration | 03 years for contract disputes

(Article 429) |

02 years

(Article 319) |

02 years, unless the specialized law provided otherwise

(Article 33) |

| Starting point | The date on which the eligible person knows or should know that its legitimate rights and interests are infringed. | The date at which the legitimate rights and interests are infringed

|

The date at which the legitimate rights and interests are infringed.

|

| Permissible exclusions | Yes, under Article 156 | Silent | Silent |

| Re-commencement | Yes, under Article 157 | Silent | Silent |

All three of the aforementioned laws may apply to resolving disputes through international arbitration. However, since their provisions on the statute of limitations differ, it is essential to analyze the applicable principles to determine the final governing rule and reach a definitive conclusion.

First of all, LCA has specified that the statute of limitations of this law is only applicable when the specialized law does not provide otherwise, therefore the Law on Commerce (or other specialized laws) would be considered for the application instead of LCA. However, for Civil Code, it should be clarified whether or not this law could be deemed a “specialized law” and considered for application.

In terms of the wording of Article 33 of LCA, Civil Code could hardly be considered as a “specialized law” to be applicable in this situation, since it is essentially the general law governing civil relations. This, however, inadvertently leads to the inapplicability of provisions on the re-commencement of statute of limitations, or permissible exclusions of statute of limitations in arbitration procedures. This would be somewhat contradictory in practice because arbitral tribunals would often cite stipulations on permissible exclusions or the re-commencement of the statute of limitations in Article 156 and Article 157 of Civil Code since LCA does not provide for these matters.[8]

In practice, the courts of Vietnam also apply provisions of the Civil Code to determine issues in relation to the statute of limitations for disputes resolved via arbitration. To be specific, in Decision No. 10/2014/QD-PQTT dated 28/10/2014, the People’s Court of Hanoi applied the provision on statute of limitations of the Civil Procedure Code (which is now provided for by Civil Code) instead of the provision of LCA to determine the statute of limitations for arbitration in a contract dispute on deposit. Prof. Do Van Dai[9] – one of the most prestigious legal scholars in Vietnam favors this approach of the courts, stated that: “This approach of the courts is a reasonable one that could remedy the flaws of the Law on Commercial Arbitration in relation to statute of limitations, and thus should be maintained in similar cases”.[10]

When both the Law on Commerce and Civil Code are applied to determine the statute of limitations, the Law on Commerce should be prioritized as this is the specialized law for commercial relations, which is also in compliance with the principles of prioritization of specialized law over general law.[11]

However, it is important to note that Commercial Law’s provisions do not govern construction contracts. Instead, Civil Code applies directly as the general law, supplementing the specialized provisions of the Construction Law. This position has been affirmed by the People’s Supreme Court in Cassation Decision No. 12/2019/DS-GDT dated 24/09/2019[12] (which is currently under research for development into precedent). Therefore, the matter of statute of limitations for construction contract disputes would be subject to the regulation of Civil Code.

In summary, depending on the specifics of each case, parties to the contract should determine which specific law of Vietnam governs statute of limitations for arbitration. Additionally, it should also be noted that the maximum duration is 03 years (if Civil Code is applied as analyzed above), with only a few limited exceptions.[13]

Identify the Starting Point of the Statute of Limitations

Another crucial aspect of statute of limitations is determining their commencement. Accurate determination of this starting point is essential for parties seeking to protect their legitimate rights and avoid the consequences of expiry.

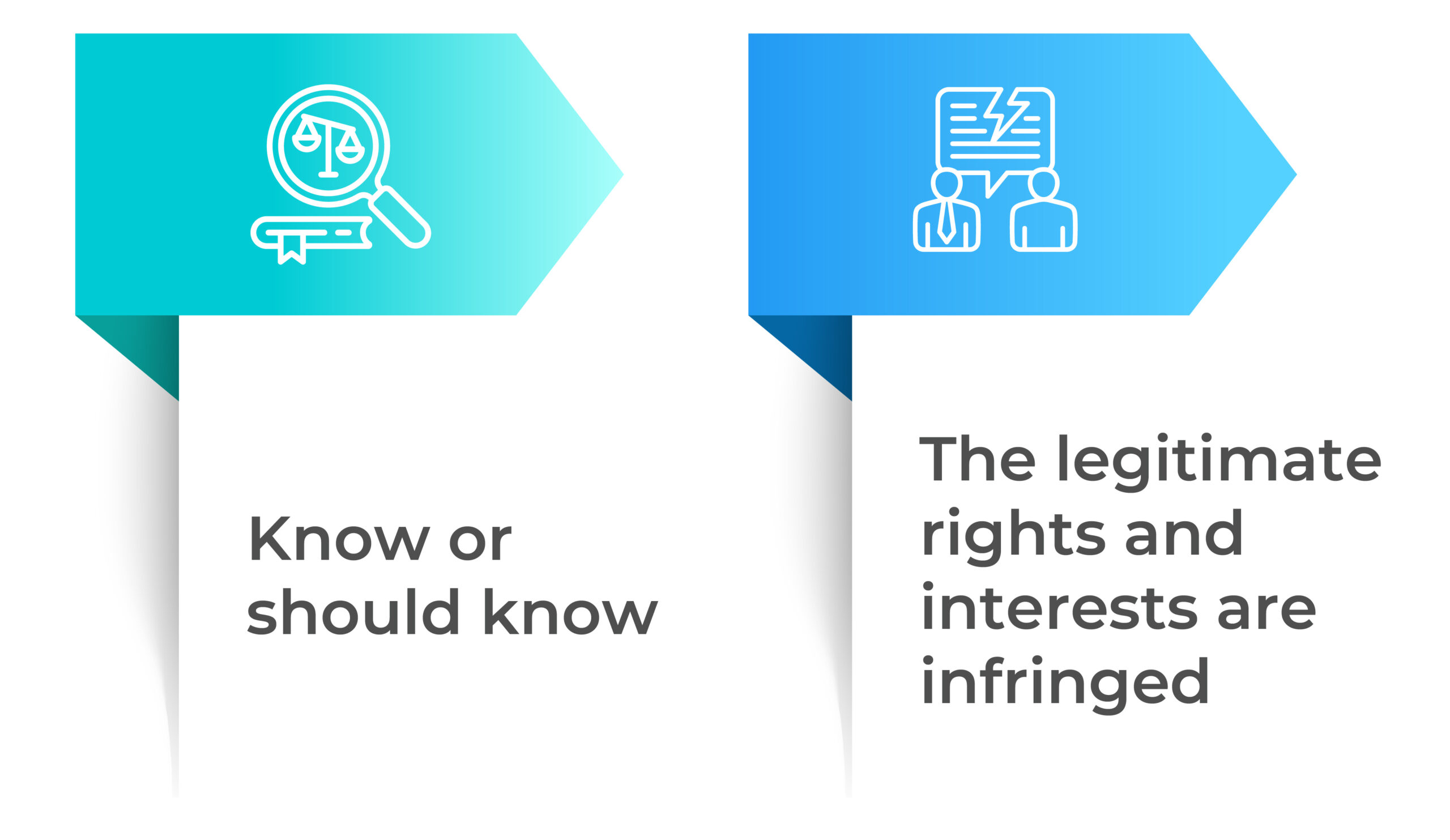

Depending on the most frequently used laws for the determination of statute of limitations as analyzed above, the starting point of statute of limitations would also be different:

- If Civil Code is applied, the statute of limitations would be commenced from the date on which the eligible person knows or should know that its legitimate rights and benefits are infringed.

- If Law on Commerce or LCA is applied, the statute of limitations would commence from the date at which the legitimate rights and benefits are infringed.

When does the statute of limitations commence?

The application of the starting point for statute of limitations as stipulated in Law on Commerce and LCA is fundamentally detrimental to the claimant since the starting point of statute of limitations is based solely on the moment at which the legitimate rights and interests are infringed, without accounting for whether the claimant knows (or should know) of such infringement. In practice, these two moments do not always coincide. For instance, in construction quality disputes, the date at which the contractor breaches the construction quality obligations due to failure to comply with the design might not coincide with the date the employer is aware of such breaches, which is often during the periodical inspection, taking over testing, or even after the handover and operation.

Therefore, to overcome the above irrationality, Civil Code has specified that the statute of limitations would only start after the eligible person knows or should know about the infringement.

However, for complicated disputes such as FIDIC – based construction contract disputes, the determination of the date at which the eligible person knows or should know about the infringement is challenging. The issue for disputing parties (as well as the arbitral tribunal) is to decide which is the starting point of the statute of limitations between the two following instances:

- Instance 1: From the date one party is entitled to claim due to the fulfillment of the conditions for such entitlement under the contract. Such as delay in the site handover by the employer, which entitles the contractor to submit claims for extension of time (and costs) to the engineer for determination.

- Instance 2: From the date one party issues the notice of dissatisfaction to object the determination of the Engineer, or from the expiration of the time limit for determination by the engineer in case there is no determination given by the engineer.

In arbitration, the respondent typically argues that the statute of limitations began at Instance 1, asserting that the claimant’s knowledge of the infringement (related to time or cost) at that point should have triggered the claim procedure with the engineer.

However, in our opinion, Instance 2 is the accurate starting point for statute of limitations, due to the following 3 reasons:

Firstly, at the time when one party is entitled to submit the notice of claim, the statute of limitations might not start as the rights of that party might not have been infringed yet. This is because FIDIC forms of contracts are designed with the mechanism to empower the engineer – as the third party that acts in a reasonable and fair manner – to review and make appropriate determinations to preserve the rights of the claiming party. Assuming that the engineer gives a determination accepting the claim and neither of the parties objects to such determination, in such cases, the rights of the claiming party are still ensured in accordance with the contract.

In other words, while a claim is under the engineer’s review and assessment pending the official determination, the rights of the claiming parties are still preserved and could not be considered infringed.

The purpose of this mechanism is to encourage appropriate resolution of claims, thus mitigating the risks of disputes between the parties. In the third edition of GAR’s The Guide to Construction Arbitration, Philip Norman and Leanie van de Merwe stated that: “Given the frequency of these types of claims, the contractual claims procedures are set up to try to resolve them expediently, in the hope that formal dispute resolution processes, such as litigation in national courts or arbitration, are avoided.”[14]

Secondly, at the time of submission of the notice of claim by one party, no dispute has occurred between the parties. In other words, in FIDIC contracts, “claim” and “dispute” are two terms with completely different meanings. Specifically, FIDIC contracts (including both 1999 and 2017 editions) have set out a 4-step procedure to resolve a claim by one party:

Procedure to resolve a claim

- Step 1: The claiming party submits the notice of claim in accordance with the contract for the engineer’s review;

- Step 2: If parties could not reach an agreement then the engineer makes its determination on the claim. If either party is not satisfied with the engineer’s determination, such party will give notice of dissatisfaction to the engineer; and

- Step 3: Parties might refer the disputes to the Dispute Adjudication Board (“DAB”) or the Dispute Avoidance/Adjudication Board (“DAAB”), depending on respective edition, for resolution;

- Step 4: If the dispute resolution at DAB/DAAB is unsuccessful (either due to having no DAB/DAAB in place or parties’ dissatisfaction with the decision), parties might refer the dispute to arbitration for resolution after having considered “amicable settlement” as a encouraged step.

With the above 4-step procedure, FIDIC contracts have differentiated the term “claim” (in step 1 and step 2) from the term “dispute” (in step 3 and step 4). Although the 1999 edition of FIDIC contracts does not provide respective definitions for “claim” and “dispute”, based on Clause 20, it is clear that a “claim” would only become a “dispute” after such a matter could not be resolved via the engineer’s determination and reference to the DAB would be required for its resolution (Sub-Clause 20.4). On this matter, Mr. Michael Mortimer-Hawkins – FIDIC Contracts Committees, stated the following when providing commentary on Clause 20 of FIDIC 1999: “A Claim is essentially a request from one party (usually the Contractor) for something which he considers is due to him under the terms of the Contract – and a Dispute arises when the other party disagrees with the Claimant either on fact or quantum, and the parties cannot reach an amicable solution.”[15]

In the 2017 edition (amended in 2022), FIDIC has clarified the matter by providing specific definitions of “claim” in Sub-Clause 1.1.6 and “dispute” in Sub-Clause 1.1.29. Accordingly, a claim would only become a dispute after that claim has been rejected (in whole or in part) by the engineer’s determination and the claiming party has issued the notice of dissatisfaction (NOD) with such engineer’s determination.

Thirdly, there is no ground to start the statute of limitations if there exists no dispute between the parties. Statute of limitations are time limits prescribed by the laws for one party to request the court (or arbitration) to protect their rights in the event of disputes (when legitimate rights and interests are infringed). Therefore, if there exists no dispute, statute of limitations could not be commenced as it would be impractical, contradictory to the purpose of statute of limitations, and adversely affecting the party whose rights are infringed when calculating the statute of limitations at an earlier time point means that the remaining time is reduced.

In short, for FIDIC-based construction contract disputes, the statute of limitations for a claim likely begins when the engineer issues (or is deemed to have issued) a determination rejecting the claim (in whole or in part), and the claimant disagrees with that rejection.

It is important to note that although the 2017 version of the FIDIC contract stipulates that the reference of a dispute to the DAAB shall be deemed to interrupt the running of statute of limitations[16], whether or not such agreements shall be recognized and respected by the arbitral tribunal (or courts) is a question left unaddressed by the laws of Vietnam. This is because Article 156 of the Civil Code on the exclusions from statute of limitations does not provide any similar stipulations (time spent on pre-proceeding dispute resolution is excluded from statute of limitations), nor does it provide any open-ended stipulations that would allow parties to agree on other cases of exclusions from statute of limitations aside from those prescribed by the law.

Exclusion or recommencement of statute of limitations

The expiration of statute of limitations is a grave issue that could result in the complete dismissal of arbitration cases from the beginning, especially when most major international arbitration institutions have procedures of early dismissal[17] or preliminary determination[18] to determine whether a case could proceed prior to the review of the content of the dispute.

In that case, the party wishing to pursue the proceedings needs to carefully consider whether there are any feasible options to overcome the hurdle of the statute of limitations. From the perspective of Vietnamese law, that party may consider, among others:

Permissible exclusions of the statute of limitations

- Whether there is any period of time excluded from the statute of limitations (permissible exclusions);

- Whether there is any event that allows the statute of limitations to be re-commenced.

Article 156.1 of the Civil Code enumerates specific circumstances under which the lapse of time is excluded from the calculation of the statute of limitations. These provisions offer potential avenues for parties to explore in assessing the applicability of statutory time limits to their particular legal action. Accordingly, the time during which a “force majeure event” or an “objective hindrance” occurs will not be counted toward the statute of limitations.

A force majeure event under Vietnamese law is applicable when it fulfills 03 conditions: (i) it occurs objective manner, (ii) not able to be foreseen, and (iii) not able to be remedied by all possible necessary and admissible measures being taken.

Meanwhile, an “objective hindrance” is generally easier to satisfy compared to a “force majeure event”, as it is only required that the event is objective and prevents the entitled party from taking legal action (whether due to not being aware of the infringement of their rights or the inability to take legal action despite being aware). For example, the event of a storm causing a delay in the claimant filing an arbitration claim (and thus missing the statute of limitations) may not meet the conditions of a “force majeure” (since storms are seasonal and the parties can anticipate them), but it may satisfy the conditions of an “objective hindrance”.

Re-commencement of statute of limitations

According to Article 157 of the Civil Code 2015, the statute of limitations shall be restarted in the following cases:

Three scenarios for the recommencement of the statute of limitations

First, the obligor acknowledges their obligation toward the claimant in whole or in part. For example, in FIDIC-based construction contracts, if the engineer gives a determination that only accepts parts of the contractor’s costs claim (and dismisses all of the remaining parts of the claim), such determination by the Engineer could be a basis to re-commence the statute of limitations for all of the Contractor’s costs claim.

Second, the obligor acknowledged or fulfilled part of its obligations toward the claimant. To Illustrate, similar to the above example, if the employer, based on the engineer’s determination (which accept a part of the contractor’s claim), made payment of the accepted cost to the Contractor, this payment could be the basis to re-commence the statute of limitations for all of the Contractor’s costs claim.

Third, the parties have become reconciled. In the event parties have become reconciled, the statute of limitations shall be refreshed from the moment parties reach settlement.

It should be noted that, in any of the above three cases, the refreshed statute of limitations shall not be affected by whether the statute of limitations has expired or not.

Conclusion

Under Vietnamese law, the characterization of the statute of limitations as substantive or procedural remains ambiguous, impacting the grounds for setting aside or refusing recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards based on alleged errors in its application. Furthermore, when Vietnamese law governs the statute of limitations in arbitration, precise identification of the applicable legal instrument (e.g., Civil Code, Commercial Law, or LCA) is crucial, as this determination carries significant legal ramifications.

In cases where a statute of limitations has prima facie expired, careful consideration of legally recognized exceptions to its calculation, such as periods excluded from the limitation or events triggering its re-commencement, becomes a critical strategic element for parties involved in dispute resolution.

Note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of CNC Vietnam Law Firm.

Written by:

|

Senior Associate I Tran Pham Hoang Tung

Phone: (84) 901 334 192 Email: tung.tran@cnccounsel.com |

|

Legal Intern I Bui Doan Minh Tri

Phone: (84) 347 924 900 Email: tri.bui@cnccounsel.com |

[1] Thiago Marinho, ‘Statute of Limitations and International Arbitration’, <https://cbar.org.br/site/statute-of-limitations-and-international-arbitration/>

[2] Brian Millar, ‘Applicable Laws for Limitation Periods: Blurring Substantive and Procedural Lines in International Commercial Arbitration?’ Kluwer Arbitration Blog < https://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2023/10/07/applicable-laws-for-limitation-periods-blurring-substantive-and-procedural-lines-in-international-commercial-arbitration-part-one/>

[3] Brian Millar, Ibid.

[4] Decision No. 11/2018/QĐ-PQTT dated 12/10/2018 of the People’s Court of Ha Noi on dismissal of request for setting aside of arbitral award.

[5] See: Do Van Dai, Phương thức giải quyết tranh chấp bằng trọng tài trong bối cảnh hội nhập kinh tế quốc tế (Hong Duc Publishing House, 2022), p. 563

[6] Do Van Dai, ‘Thời hiệu khởi kiện trong lĩnh vực trọng tài – Kinh nghiệm quốc tế cho Việt Nam’ Law Journal (No 4/2021), p. 49-50.

[7] Article 71.4 of LCA and Article 458.4 Civil Procedure Code 2015

[8] Ngo Khac Le, ‘Tranh chấp về thời hiệu khởi kiện’ (10/11/2020) VIAC < https://www.viac.vn/goc-nhin-trong-tai-vien/tranh-chap-ve-thoi-hieu-khoi-kien-a992.html>

[9] Vice Rector of the Ho Chi Minh City University of Law, Vice President of the Legal Science Council of the Vietnam International Arbitration Center, member of the Precedent Advisory Council of the People’s Supreme Court.

[10] Prof. Do Van Dai, The laws on commercial arbitration in Vietnam – Judgments and Judgment commentary (Volume 1) (Hong Duc Publishing House, 2017), p. 288

[11] This principle is specified in Article 4.2 of Civil Code and Article 4.3 of Law on Commerce.

[12] Cassation Decision No. 12/2019/DS-GDT dated 24/09/2019 of the People’s Supreme Court on Indemnity Disputes regarding a rock excavation contract.

[13] No statute of limitations would be applied to disputes in relation to the protection of ownership rights as specified in Article 155.2, Civil Code 2015.

[14] Philip Norman and Leanie van de Merwe, Covington & Burling, Claims Resolution Procedures in Construction Contracts (Third edition of GAR’s The Guide to Construction Arbitration)

[15] Michael Mortimer-Hawkins, ‘Clause 20, Dispute Resolution’ FIDIC Contracts Committee <https://fidic.org/sites/default/files/24%20CLAUSE%2020,%20DISPUTE%20RESOLUTION.pdf>

[16] The final paragraph of Article 21.4.1 FIDIC Red Book 2017

[17] Such as ICC Rules 2021 (Section VII, Item D, paragraph 110 of ICC Note to parties and arbitral tribunals on the conduct of arbitration under the ICC Rules of Arbitration), SIAC Rules 2025 (Rule 34), LCIA Rules 2020 (Article 22.1(viii))

[18] Such as SIAC Rules 2025 (Rule 46), HKIAC Rules 2024 (Article 13.6)