Distinction between jurisdiction and admissibility in international arbitration

The distinction between jurisdiction and admissibility in international arbitration is a contentious issue in contemporary arbitral practice, particularly as multi-tiered dispute resolution clauses become increasingly prevalent. This distinction, though challenging, is of paramount importance due to its impact on the validity of arbitral awards and the parties’ expectations for a fair and transparent resolution of disputes. This article aims to elucidate the basis for determining jurisdiction and admissibility in arbitration, the fundamental legal consequences of distinguishing between them, and the variations in their delineation across different jurisdictions.

Definition

Jurisdiction of Arbitration

The jurisdiction of an arbitral tribunal refers to its authority to issue a decision that affects the substance of a dispute.[1] The existence of arbitral jurisdiction is due to the parties’ mutual consent. Without an agreement to resolve disputes through arbitration, the arbitral process cannot be automatically invoked.[2] Additionally, the tribunal’s jurisdiction is subject to certain constraints imposed by the applicable law governing the arbitration agreement and the law of the place where the arbitration is conducted.[3]

Admissibility

Admissibility refers to the suitability of a claim for resolution through arbitration, enabling the tribunal to exercise its jurisdiction.[4] It is often showcased in multi-tiered arbitration clauses, where preliminary steps such as negotiation or mediation might be required before a dispute can be settled by arbitration. Admissibility concerns the appropriateness of the request for arbitration, such as whether a claimant’s failure to attempt mediation, as stipulated in a multi-tiered clause, renders the request for arbitration inadmissible.[5]

The distinction of jurisdiction and admissibility in countries

The approach to distinguishing between jurisdiction and admissibility varies across countries. In some countries such as France, the United Kingdom and Hong Kong, the appropriateness of a claim for arbitration is treated as an issue of admissibility which is distinct from the conditions determining the tribunal’s jurisdiction and thus does not affect the tribunal’s authority. For instance, in the case C v D [2022] 3 HKLRD 116, the Hong Kong High Court held that the arbitral tribunal’s determination regarding the appropriateness of a claim was an issue of admissibility. Consequently, even though the parties failed to negotiate in good faith prior to initiating arbitration as agreed, the court did not entertain the claimant’s request to set aside the arbitral award as the tribunal’s decision on admissibility was deemed final.[6]

On the contrary, other jurisdictions consider the appropriateness of a claim as a condition for establishing the tribunal’s jurisdiction. Failure to comply with the preliminary steps outlined in multi-tiered dispute resolution clauses may result in the tribunal lacking jurisdiction. For example, in X Ltd v Y SpA, 4A_628/2015, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court ruled that a decision on whether an arbitral tribunal could proceed with a dispute in the event of non-compliance with multi-tiered dispute resolution steps was a matter of jurisdiction.[7]

In Vietnam, under the Law on Commercial Arbitration (LCA), the determination of arbitral jurisdiction is based on criteria such as the subject matter or parties to the dispute: “Disputes arising from commercial activities; disputes where at least one party engages in commercial activities” and the existence of an arbitration agreement: “Disputes shall be resolved by arbitration if the parties have an arbitration agreement.”[8] However, preliminary procedural requirements are not explicitly addressed. As a result, issues related to admissibility remain unclear and contentious in Vietnam.

Determination of jurisdiction and admissibility

The framework for the determination of arbitral jurisdiction

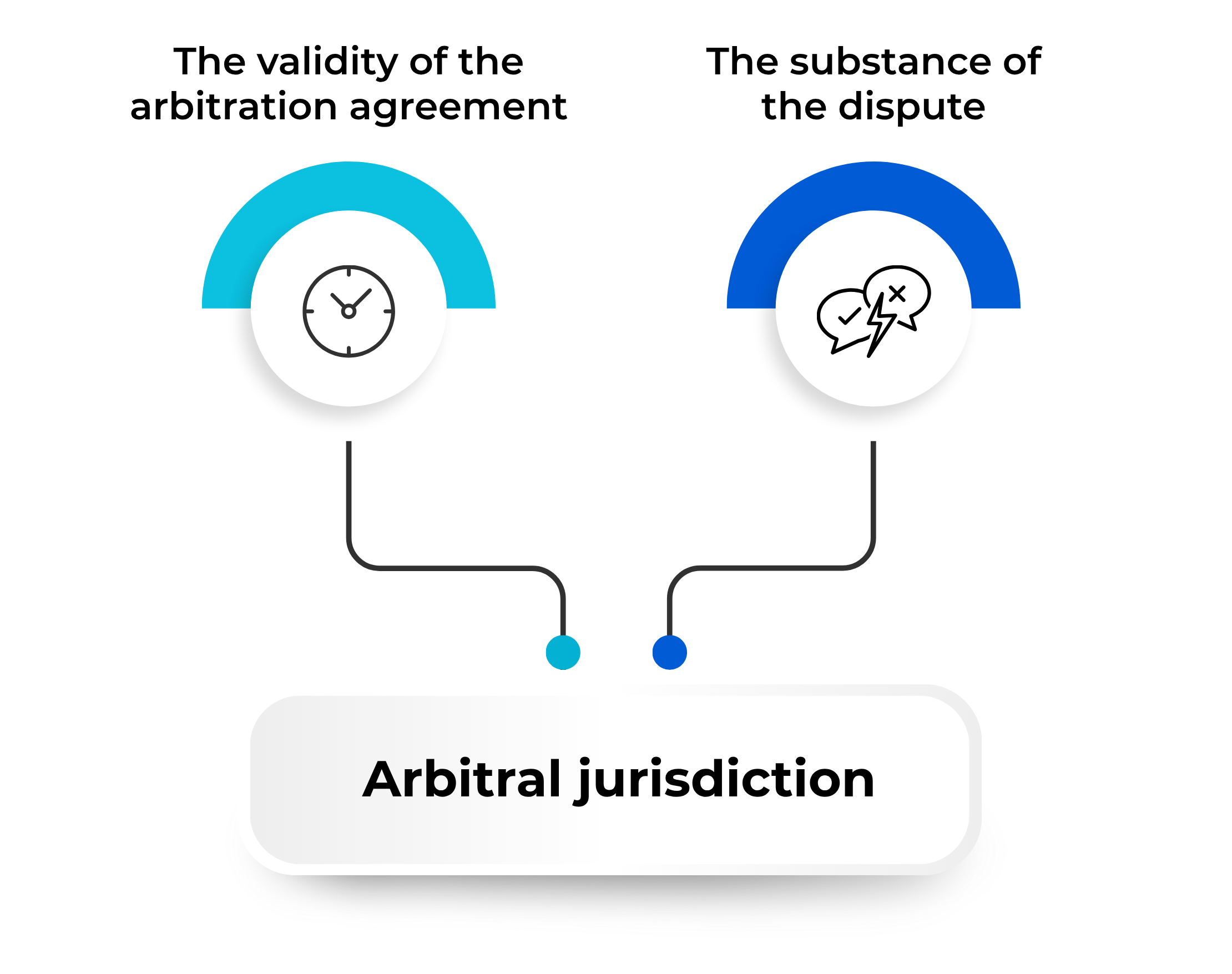

The determination of arbitral jurisdiction varies depending on the arbitration laws of each jurisdiction. Key criteria include:

(i) The validity of the arbitration agreement

A valid arbitration agreement must meet fundamental requirements, such as being entered into voluntarily by parties with the requisite authority, being in written form (either as a clause in a contract or a separate agreement), having disputes to be resolved through arbitration clearly identified, and possessing arbitrability.

(ii) The substance of the dispute

After confirming the validity of the arbitration agreement, the arbitral tribunal must determine whether the claims raised by the parties fall within the scope of disputes agreed to be resolved by arbitration. If the arbitration agreement is a clause within a contract, claims related to the contract are generally presumed to fall within the tribunal’s jurisdiction.[9]

Jurisdictional basis of the arbitral tribunal

Common elements affecting admissibility

Unlike jurisdiction which may be governed by applicable arbitration laws, admissibility is determined solely at the discretion of the arbitral tribunal, therefore making it difficult to establish universal principles. However, based on global arbitral practice, the clarity of multi-tiered dispute resolution clauses often plays a critical role in the tribunal’s decision-making process. For instance, if the parties explicitly agree that steps such as negotiation or mediation are mandatory before resorting to arbitration, the tribunal may require compliance with these steps before proceeding with the dispute resolution.[10]

Legal consequences of the determination of jurisdiction and admissibility

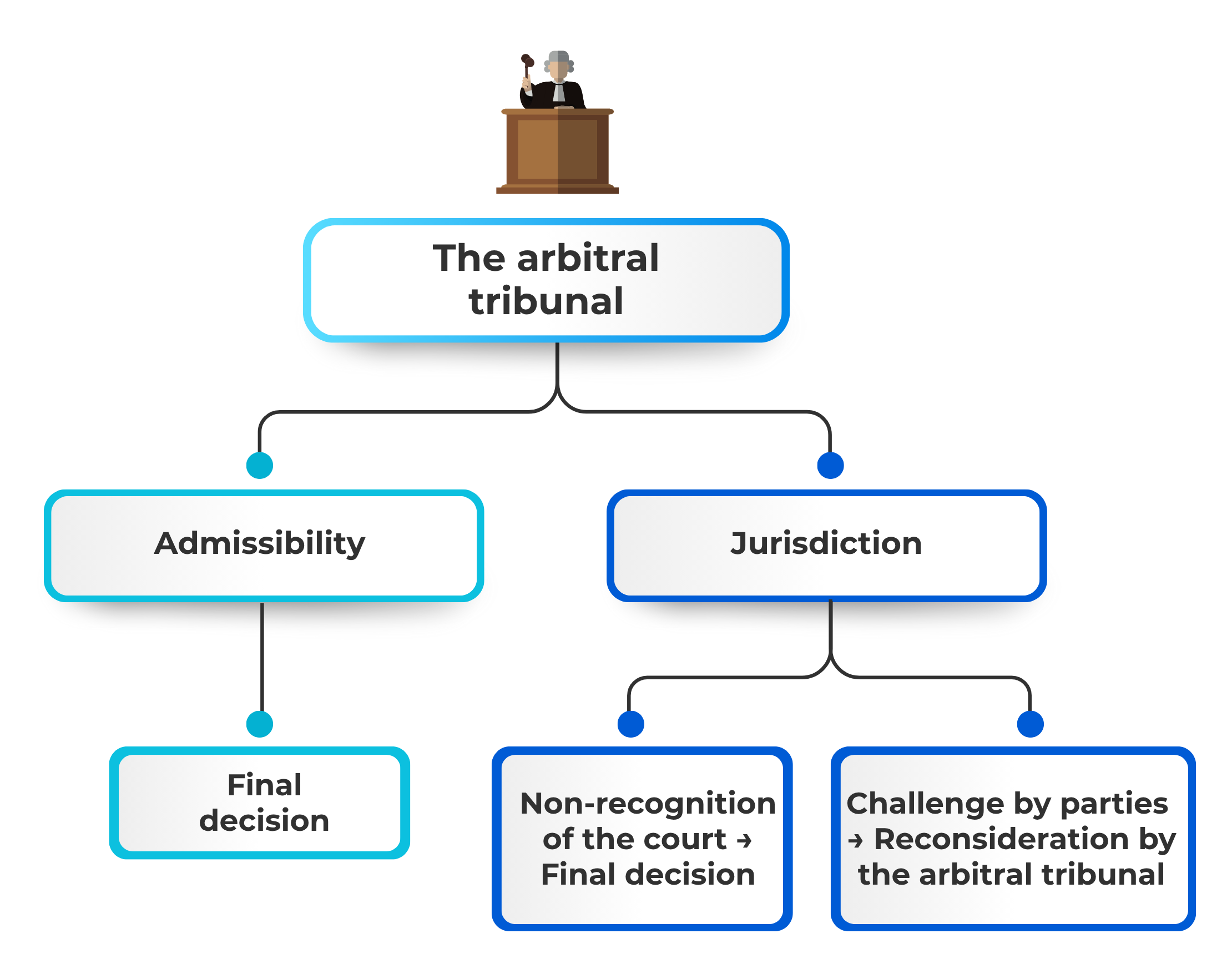

Legal consequences of the determination of arbitral jurisdiction

One of the cornerstone principles of international commercial arbitration is “competence-competence” which allows an arbitral tribunal to determine its own jurisdiction. This principle is enshrined in Article 43(1) of Vietnam’s LCA: “Before considering the circumstances of a dispute, the arbitration council shall consider the validity of the arbitration agreement and whether such agreement can be realized, and consider its jurisdiction.” The validity of the arbitration agreement is evaluated under the separability principle, which treats the arbitration agreement as a separate contract, independent of the main contract in which it is contained.[11] However, the tribunal’s decision on jurisdiction is not final and may subject to review by a third party[12], typically the court in the country where the arbitration is settled (seat of arbitration). This is because the tribunal’s authority derives from the parties’ consent, as expressed in the arbitration agreement as well as the applicable arbitration law. Specifically:

(i) A party to the dispute may challenge the tribunal’s jurisdiction, and the tribunal is obliged to reconsider its jurisdiction. The right to challenge jurisdiction also aligns with the “competence-competence” principle, which aims to minimize disruptions in arbitral proceedings while preserving the parties’ right to object to jurisdiction on valid grounds. [13]This is further clarified in Article 43(2) of the LCA: “In the course of dispute settlement, if it is detected that the arbitration council commit ultra vires acts, the parties may lodge a complaint with the arbitration council. The arbitration council shall consider and decide on this issue.”

(ii) Courts have the ultimate authority to make a final determination on the tribunal’s jurisdiction. If a court does not recognize the arbitration agreement, it shall assume jurisdiction over the dispute in place of the arbitral tribunal.[14]

Regarding admissibility, the arbitral tribunal has the authority to determine whether a claim is admissible, and its decision is final. This is because admissibility is assessed within the scope of the tribunal’s jurisdiction, occurring only after the tribunal has confirmed its authority over the dispute.[15] In Vietnam, while there is no explicit legal provision granting arbitral tribunals the authority to determine admissibility at the moment, most tribunals undertake this assessment in practice.[16]

Jurisdiction to determine issues of jurisdiction and admissibility

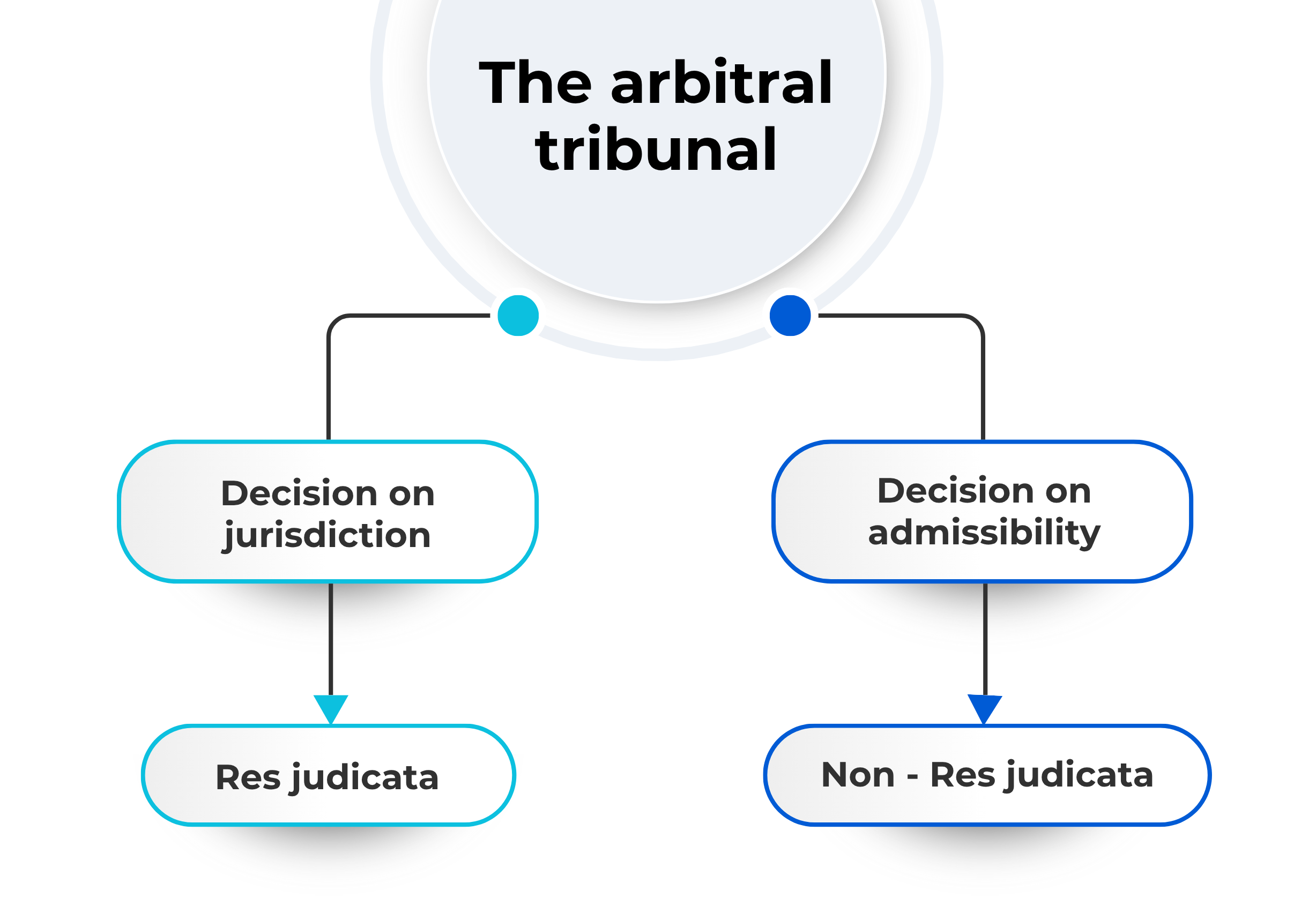

The res judicata principle

The res judicata principle stipulates that once a binding decision has been issued by a competent adjudicatory body, the parties are precluded from re-litigating the same matter unless there is a change in the parties, the subject matter, or the legal basis of the dispute (triple-identity criteria).[17]

In arbitral practice, this principle is applied differently in the context of jurisdiction and admissibility. A tribunal’s decision that a dispute falls outside its jurisdiction carries res judicata effect, preventing the parties from re-submitting the same claim to the same tribunal. On the other hand, a decision that a claim is inadmissible does not carry “res judicata” effect and may be re-submitted once preliminary procedural barriers (e.g., waiting periods or exhaustion of local remedies) are resolved.[18] A notable example in investment arbitration is the Abaclat v. Argentina case, where the tribunal concluded that “whereby a final refusal based on a lack of jurisdiction will prevent the parties from successfully re-submitting the same claim to the same body, a refusal based on admissibility will, in principle, not prevent the claimant from re-submitting its claim, provided it cures the previous flaw causing the inadmissibility”[19]

Distinguishing the nature of jurisdiction and admissibility

Conclusion

The determination of jurisdiction and admissibility in arbitration depends on the legal framework of each jurisdiction. In Vietnam, the lack of clear regulations on admissibility creates significant controversies and practical challenges. The most significant legal consequence of this distinction lies in whether the final decision-making authority rests with the arbitral tribunal or the courts. Clarifying this distinction prior to the formal dispute solution through arbitration is essential to minimize the risk of subsequent set aside of arbitral awards.

Writen by

|

Tran Pham Hoang Tung I Partner

Phone: (84) 901 334 192 Email: tung.tran@cnccounsel.com |

|

Pham Ngoc Thanh Tra I Collaborator

Phone: (84) 347 924 900 |

[1] Andrew Tweeddale (2021), ‘Jurisdiction and admissibility in dispute resolution clauses’, Construction Law International, 16 (1), 13 – 17, <Jurisdiction and admissibility in dispute resolution clauses | International Bar Association>

[2] Nigel Blackaby, Constatine Partasides QC, Alan Redfern, Martin Hunter, Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration (Sixth Edition), Oxford University (2015), paragraph 5.91

[3] Nigel Blackaby, Constatine Partasides QC, Alan Redfern, Martin Hunter, supra note 2, paragraph 3.37 – 3.48

[4] August Reinisch, ‘Jurisdiction and Admissibility in International Investment Law’, Jurisdiction and Admissibility in International Investment Law, 2, <https://icsid.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/parties_publications/C8394/Claimants’%20documents/CL%20-%20Exhibits/CL-0454.pdf > accessed on 01/7/2025

[5] Nguyen Manh Tuan (2023), ‘Thẩm quyền quyết định hiệu lực thi hành của thỏa thuận tiền tố tụng trọng tài’, Tạp chí Tòa án nhân dân, <https://tapchitoaan.vn/tham-quyen-quyet-dinh-hieu-luc-thi-hanh-cua-thoa-thuan-tien-to-tung-trong-tai9880.html> accessed on 10/12/2024

[6] Dantes Leung, Davis Hui (2023), ‘Making Sense of Jurisdiction-Admissibility Distinction: When Day Becomes Night’, Hong Kong Lawyer, <https://www.hk-lawyer.org/content/making-sense-jurisdiction-admissibility-distinction-when-day-becomes-night>

[7] ibid

[8] Article 2.1 of Resolution No. 01/2014/NQ-HĐTP

[9] Dena Givari (2024), ‘Commercial Litigation Insights: A Framework for Arbitrators to Determine Jurisdiction’, WeirFoulds LLP <https://www.weirfoulds.com/commercial-litigation-insights-a-framework-for-arbitrators-to-determine-jurisdiction>

[10] Kevin Cheung (2022), ‘Pre-conditions to arbitration: admissibility v jurisdiction approaches from England and Hong Kong’, Thomson Reuters, <http://arbitrationblog.practicallaw.com/pre-conditions-to-arbitration-admissibility-v-jurisdiction-approaches-from-england-and-hong-kong/>

[11] Doug Jones (2009), ‘Competence – Competence’, 75 Arbitration 56 – 64, 56 – 57, <https://dougjones.info/content/uploads/2023/04/460-Competence-Competence.pdf>

[12] Jan Paulsson (2005), ‘ Jurisdiction and Admissibility’, Global Reflections on International Law, Commerce and Dispute Resolution, 693, 601, <https://cdn.arbitration-icca.org/s3fs-public/document/media_document/media012254599444060jasp_article_-_jurisdiction_and_admissibility_-_liber_amicorum_robert_briner.pdf>

[13] Doug Jones, supra note 11

[14] Article 2.3.a of Resolution No. 01/2014/NQ-HDTP

[15] Jan Paulsson, supra note 12, 601 – 604

[16] Kevin Cheung, supra note 10

[17] ‘Res Judicata in International Arbitration’ Aceris Ris LLC, <https://www.acerislaw.com/res-judicata-in-international-arbitration/>

[18] Andrew Tweeddale, supra note 1

[19] Simranjit Kaur (2020), ‘The Distinction between Jurisdiction and Admissibility in International Investment Law’, Master Programme in Investment Treaty Arbitration Master’s Thesis 15 ECTS, 28 – 29, <https://www.diva portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1436202/FULLTEXT01.pdf>